Post by ChrisB on Mar 27, 2016 16:41:31 GMT

I became interested in Hartley drivers because of the Mark Levinson HQD system (the H stood for Hartley (bass) / Q for Quad (2x57's per channel) / D for Decca-Kelly (ribbons). I then became even more interested when I discovered that they did a 24" unit!

I've never heard any of these speakers, but would love the opportunity to do so.

Hartley wrote several influential books on audio:

Hartley, H.A. Audio Design Handbook, (Gernsback Library)

This is actually out of print but available on-line at blueguitar.org:

Audio Design Handbook - Pages 1-51

Pages 52-75

Pages 76-171

Pages 172-224

Hartley, H.A. New Notes in Radio – A Complete Guide to High Fidelity Reproduction

Hartley, H.A. Realistic High Fidelity

He also wrote a book about astrology!

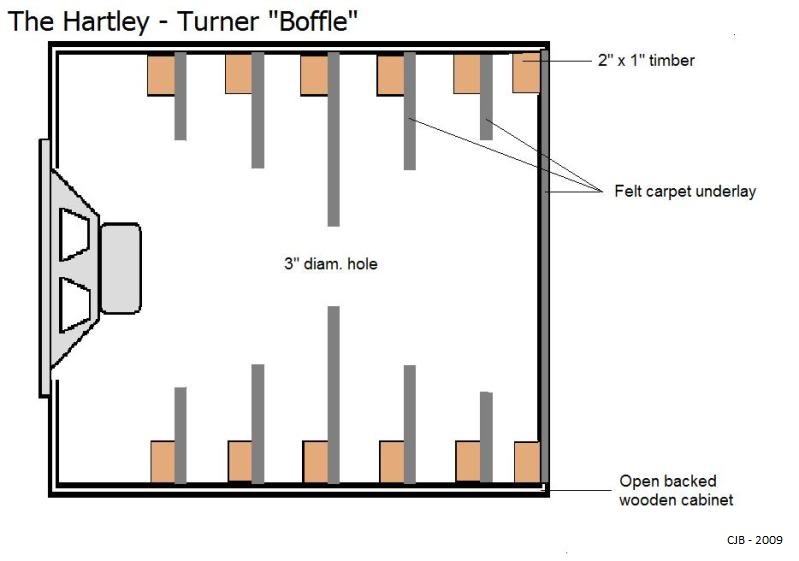

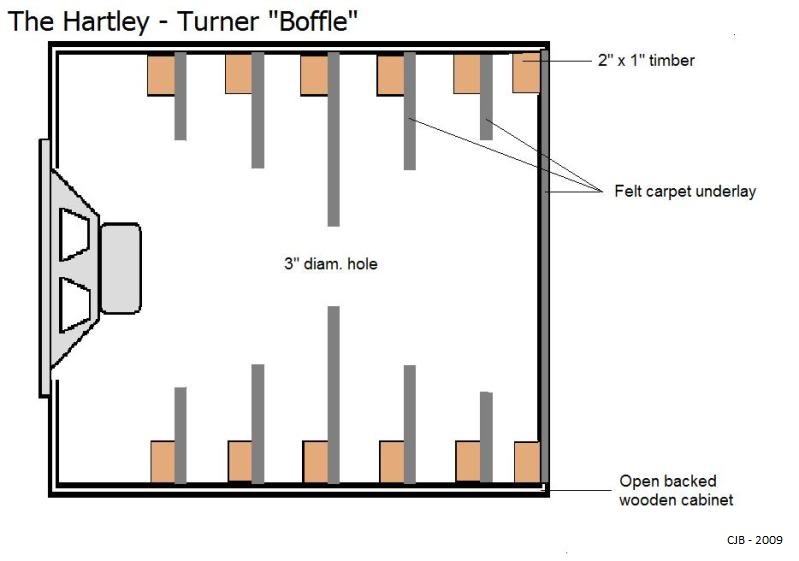

The following are extracts of a piece that I wrote elsewhere - the diagram is my own:

H. A. Hartley was the man who first coined the phrase 'high fidelity' It was originally a UK company, founded by him and P.K. Turner, but they did well in export sales. He wrote a book about how to do it, in fact, & sold all the manufacturing rights to his US distributor when he retired.

At one point, the manufacturing capacity of the company was a mere 3 drivers per day & the advertising that they published said:

Hartley drivers are fairly unique in that they don't have a join between cone & surround – the polymer mixture is poured onto the mould from the centre outwards and as the edge is reached, the mixture is seamlessly replaced from polymer to silicon rubber. The cones themselves also have a series of internally moulded rib sections.

The Hartley woofers feature an aluminium heat sink which takes the form of an extension of the tube former that the voice coil is wound on. This extends forward from the centre of the driver in order for the heat generated in the coil to be safely dissipated into the atmosphere.

The company still makes a range of 5 drive units –

207 MSG – A 7" mid range/tweeter unit (8 Ohm)

220 MSG – A 10" full range unit ((6 Ohm)

220 HS – A 10" bass unit (5 Ohm)

218 HS – An 18" bass driver (5 Ohm)

224 HS – A 24" bass driver (5 Ohm)

Hartley designed and sold his 'Boffle' speaker, which was apparently the first attempt to remove the effects of the rear bass radiation from speaker cones. The design was a box containing a series of spaced baffles behind the main driver. The baffles were wooden frames with felt carpet underlay stretched across them. Each baffle had a different sized hole cut in it - the first being just behind the driver had a diameter a little smaller than the driver diameter. The second and third were reduced successively in diameter down to 3 inches. The fourth & fifth baffles had progressively larger holes in them & the final one didn't have a hole.

Two historical reviews of The Boffle

The Hartley-Turner Boffle

The Hartley-Turner boffle sets out to absorb as much as possible of the sound produced from the back of the speaker and at the same time to prevent the wood of the box from being set into vibration.

It succeeds in both objects. At regular intervals across the inside of the boffie sheets of sound-absorbing material are stretched. In the centre of each sheet a hole is cut, the holes decreasing in size from the back of the speaker to the back of the box, the air column thus formed being approximately exponential. There is thus the equivalent of an exponential air column behind the horn (which itself is useful in imposing an acoustic load on the cone), and in addition a series of air cavities between the absorbent sheets to act as a sound absorbing wave-filter.

So successful is the arrangement that with the speaker working at large volume only very faint sounds, and those of very low pitch, can be heard coming from the back of the speaker even when the ear is placed within a few inches of the back of the boffle ; whilst to the touch the boffle itself is as dead as the proverbial mutton. All within an 18-inch cube, mind you.

We understand that other sizes of boifie are available. One measures 18 in. by 18 in. by 12 in. and costs £2. Another measures 21-inch cube and costs £3 15s.

There can be no doubt that this boffle is a substantial contribution to loudspeaker design and to the cause of undefiled reproduction generally.

Gramophone Magazine – March 1935

Hartley H.F. Speaker 215 and Hartley- Turner Boffle.

Prices ; Speaker £14 10s plus £4 4s 3d. Boffle £8.

This Loudspeaker with its associated Boffle (which, of course' is a Lewis Carroll word for Box-Baffle), have long regarded as the problem child of the loudspeaker family. Not because I do not think it good, because in fact I think it very good indeed ; but because it poses quite a number of questions and I am not satisfied as to the answers to many of them.

Before I go on to mention some of these posers for the benefit of more technically minded readers, I had better say a few words about the performance as I have found it during the past three months in the tests I have made in my own home.

In all forms of speaker cabinet that I have yet heard there seems to be a certain amount of coloration when low and high notes are sounding together. This is quite obvious when one tests them alongside (or preferably in an adjacent room to) a speaker mounted on a carefully designed infinite baffle such as I have in the 16 inch wall between my workroom and drawing room ; and particularly on passages of considerable volume, when in all cabinets the instruments seem somehow to run together and form a conglomerate mass. There is a certain spatial effect, too, which is observable with an infinite baffle but which is almost completely absent in a cabinet enclosure. And if the reproduction 'gees deep into the bass, that is down to 30 c/s or so (which is some three octaves below Middle C) there is a rich, soft quality obtainable from the baffle which is not evident from a cabinet.

The Hartley-Turner Boffle was designed to approximate to the conditions of an infinite baffle. The leaflet supplied by the makers describes the way in which sounds from the back of the speaker are absorbed by an acoustic filter, and the way in which the Boffle approximates to the theoretical ideal.

That it actually does do this I can demonstrate at once : there is the same absence of coloration and something of the same spatial effect, and in the case of speech there is the same feeling of "presence". The one thing that I did not get to anything like the same degree was the deep softness I have mentioned, and this, as I have said, I have never heard save on a true infinite baffle. This quality, by the way, is most easily recognised in good pianoforte reproduction. The Moonlight Sonata is an excellent piece for demonstrating it ; either the Columbia Gieseking or the Decca/Backhaus record will do.

My first tests (see THE GRAMOPHONE for March, 1937) of the boffle were made with the original Hartley-Turner speaker. My present ones have been made with the 215. Now the latter is a much better speaker unit than the original, good as that was for its day. It goes much higher in the treble and deeper in the bass, and its response is smoother all the way up the scale. The arrangement inside the Boffle has also been improved with the result that there is now definitely more absorption of bass notes below 100 c/s from the back of the speaker. This is fortunate as it now makes less difference than it used to do how much space is left between the back of the Boffle and the wall of the room. The Boffle can therefore be more conveniently mounted in any type of decorative cabinet, such as a bookcase or writing bureau; in its elementary form it is a plain cube of 18 inch side.

Now the 215 speaker unit has rather surprising characteristics. It is of the first type that I mentioned last month ; that is, it attempts to cover the whole of the musical scale with one single diaphragm and coil assembly. And it succeeds remarkably well.

The 9 inch cone is flared and has a particularly free type of centring ; the amplitude of motion when I put on a 25 c/s record was of the order of 1 inch and there was no sign of distress. The surround resonance was not very prominent but I eventually traced it at about 33 c/s with more pronounced octave and double octave effects. The cone itself is divided into two major parts. The inner part has more flare than an exponential curve—it is more like a tractrix. Then comes a more flexible portion followed by slightly dished saucer outside annulus, with three concentric corrugations. Outside that there is a soft cloth surround.

The voice coil is wound on a flexible sheath over an aluminium former and is not itself directly connected to the cone. There is thus, as it were, a twofold mechanical crossover. At low frequencies the whole assembly moves as a unit, so it is claimed, whilst at high frequencies the inner flared cone is driven by the aluminium former ; and the outer elements both in voice coil and in cone serve as damping elements to absorb the vibrations and prevent back reflection and the setting up of negative waves.

Whether that action is as complete or even as useful as it is claimed I am not sure. But my observations certainly show that something of the sort does take place. The fact that there is an appreciable output at 10 kc/s and above from a 9 inch diaphragm at 400 c/s and below with a 4 inch voice coil is a testimony to the effectiveness of the design that cannot be ignored. So, too, is the comparative absence of intermodulation distortion.

In short, this is a speaker with not one but many novel and challenging ideas behind it. I propose myself to follow them up much further than I have done in the past and will write again about them later. In the meantime, though I do not altogether feel able to subscribe to some of the analysis of loudspeaker characteristics which we are told has gone into the design of this unit, I can certainly bear witness to the success of the design as a whole in giving a high degree of realism in musical sound reproduction. In that it is definitely one of the few units that enthusiasts for what is called "high fidelity" must consider.

Gramophone Magazine – May 1954

I've never heard any of these speakers, but would love the opportunity to do so.

Hartley wrote several influential books on audio:

Hartley, H.A. Audio Design Handbook, (Gernsback Library)

This is actually out of print but available on-line at blueguitar.org:

Audio Design Handbook - Pages 1-51

Pages 52-75

Pages 76-171

Pages 172-224

"I invented the phrase "high fidelity" in 1927 to denote a type of sound reproduction that might be taken rather seriously by a music lover. In those days the average radio or phonograph equipment sounded pretty horrible but, as I was really interested in music, it occurred to me that something might be done about it."

Hartley, H.A. New Notes in Radio – A Complete Guide to High Fidelity Reproduction

Hartley, H.A. Realistic High Fidelity

He also wrote a book about astrology!

The following are extracts of a piece that I wrote elsewhere - the diagram is my own:

H. A. Hartley was the man who first coined the phrase 'high fidelity' It was originally a UK company, founded by him and P.K. Turner, but they did well in export sales. He wrote a book about how to do it, in fact, & sold all the manufacturing rights to his US distributor when he retired.

At one point, the manufacturing capacity of the company was a mere 3 drivers per day & the advertising that they published said:

"Please don't pass this on to a friend.

Almost no-one knows Hartley speakers and we'd like to keep it that way".

Almost no-one knows Hartley speakers and we'd like to keep it that way".

Hartley drivers are fairly unique in that they don't have a join between cone & surround – the polymer mixture is poured onto the mould from the centre outwards and as the edge is reached, the mixture is seamlessly replaced from polymer to silicon rubber. The cones themselves also have a series of internally moulded rib sections.

The Hartley woofers feature an aluminium heat sink which takes the form of an extension of the tube former that the voice coil is wound on. This extends forward from the centre of the driver in order for the heat generated in the coil to be safely dissipated into the atmosphere.

The company still makes a range of 5 drive units –

207 MSG – A 7" mid range/tweeter unit (8 Ohm)

220 MSG – A 10" full range unit ((6 Ohm)

220 HS – A 10" bass unit (5 Ohm)

218 HS – An 18" bass driver (5 Ohm)

224 HS – A 24" bass driver (5 Ohm)

Hartley designed and sold his 'Boffle' speaker, which was apparently the first attempt to remove the effects of the rear bass radiation from speaker cones. The design was a box containing a series of spaced baffles behind the main driver. The baffles were wooden frames with felt carpet underlay stretched across them. Each baffle had a different sized hole cut in it - the first being just behind the driver had a diameter a little smaller than the driver diameter. The second and third were reduced successively in diameter down to 3 inches. The fourth & fifth baffles had progressively larger holes in them & the final one didn't have a hole.

Two historical reviews of The Boffle

The Hartley-Turner Boffle

The Hartley-Turner boffle sets out to absorb as much as possible of the sound produced from the back of the speaker and at the same time to prevent the wood of the box from being set into vibration.

It succeeds in both objects. At regular intervals across the inside of the boffie sheets of sound-absorbing material are stretched. In the centre of each sheet a hole is cut, the holes decreasing in size from the back of the speaker to the back of the box, the air column thus formed being approximately exponential. There is thus the equivalent of an exponential air column behind the horn (which itself is useful in imposing an acoustic load on the cone), and in addition a series of air cavities between the absorbent sheets to act as a sound absorbing wave-filter.

So successful is the arrangement that with the speaker working at large volume only very faint sounds, and those of very low pitch, can be heard coming from the back of the speaker even when the ear is placed within a few inches of the back of the boffle ; whilst to the touch the boffle itself is as dead as the proverbial mutton. All within an 18-inch cube, mind you.

We understand that other sizes of boifie are available. One measures 18 in. by 18 in. by 12 in. and costs £2. Another measures 21-inch cube and costs £3 15s.

There can be no doubt that this boffle is a substantial contribution to loudspeaker design and to the cause of undefiled reproduction generally.

Gramophone Magazine – March 1935

Hartley H.F. Speaker 215 and Hartley- Turner Boffle.

Prices ; Speaker £14 10s plus £4 4s 3d. Boffle £8.

This Loudspeaker with its associated Boffle (which, of course' is a Lewis Carroll word for Box-Baffle), have long regarded as the problem child of the loudspeaker family. Not because I do not think it good, because in fact I think it very good indeed ; but because it poses quite a number of questions and I am not satisfied as to the answers to many of them.

Before I go on to mention some of these posers for the benefit of more technically minded readers, I had better say a few words about the performance as I have found it during the past three months in the tests I have made in my own home.

In all forms of speaker cabinet that I have yet heard there seems to be a certain amount of coloration when low and high notes are sounding together. This is quite obvious when one tests them alongside (or preferably in an adjacent room to) a speaker mounted on a carefully designed infinite baffle such as I have in the 16 inch wall between my workroom and drawing room ; and particularly on passages of considerable volume, when in all cabinets the instruments seem somehow to run together and form a conglomerate mass. There is a certain spatial effect, too, which is observable with an infinite baffle but which is almost completely absent in a cabinet enclosure. And if the reproduction 'gees deep into the bass, that is down to 30 c/s or so (which is some three octaves below Middle C) there is a rich, soft quality obtainable from the baffle which is not evident from a cabinet.

The Hartley-Turner Boffle was designed to approximate to the conditions of an infinite baffle. The leaflet supplied by the makers describes the way in which sounds from the back of the speaker are absorbed by an acoustic filter, and the way in which the Boffle approximates to the theoretical ideal.

That it actually does do this I can demonstrate at once : there is the same absence of coloration and something of the same spatial effect, and in the case of speech there is the same feeling of "presence". The one thing that I did not get to anything like the same degree was the deep softness I have mentioned, and this, as I have said, I have never heard save on a true infinite baffle. This quality, by the way, is most easily recognised in good pianoforte reproduction. The Moonlight Sonata is an excellent piece for demonstrating it ; either the Columbia Gieseking or the Decca/Backhaus record will do.

My first tests (see THE GRAMOPHONE for March, 1937) of the boffle were made with the original Hartley-Turner speaker. My present ones have been made with the 215. Now the latter is a much better speaker unit than the original, good as that was for its day. It goes much higher in the treble and deeper in the bass, and its response is smoother all the way up the scale. The arrangement inside the Boffle has also been improved with the result that there is now definitely more absorption of bass notes below 100 c/s from the back of the speaker. This is fortunate as it now makes less difference than it used to do how much space is left between the back of the Boffle and the wall of the room. The Boffle can therefore be more conveniently mounted in any type of decorative cabinet, such as a bookcase or writing bureau; in its elementary form it is a plain cube of 18 inch side.

Now the 215 speaker unit has rather surprising characteristics. It is of the first type that I mentioned last month ; that is, it attempts to cover the whole of the musical scale with one single diaphragm and coil assembly. And it succeeds remarkably well.

The 9 inch cone is flared and has a particularly free type of centring ; the amplitude of motion when I put on a 25 c/s record was of the order of 1 inch and there was no sign of distress. The surround resonance was not very prominent but I eventually traced it at about 33 c/s with more pronounced octave and double octave effects. The cone itself is divided into two major parts. The inner part has more flare than an exponential curve—it is more like a tractrix. Then comes a more flexible portion followed by slightly dished saucer outside annulus, with three concentric corrugations. Outside that there is a soft cloth surround.

The voice coil is wound on a flexible sheath over an aluminium former and is not itself directly connected to the cone. There is thus, as it were, a twofold mechanical crossover. At low frequencies the whole assembly moves as a unit, so it is claimed, whilst at high frequencies the inner flared cone is driven by the aluminium former ; and the outer elements both in voice coil and in cone serve as damping elements to absorb the vibrations and prevent back reflection and the setting up of negative waves.

Whether that action is as complete or even as useful as it is claimed I am not sure. But my observations certainly show that something of the sort does take place. The fact that there is an appreciable output at 10 kc/s and above from a 9 inch diaphragm at 400 c/s and below with a 4 inch voice coil is a testimony to the effectiveness of the design that cannot be ignored. So, too, is the comparative absence of intermodulation distortion.

In short, this is a speaker with not one but many novel and challenging ideas behind it. I propose myself to follow them up much further than I have done in the past and will write again about them later. In the meantime, though I do not altogether feel able to subscribe to some of the analysis of loudspeaker characteristics which we are told has gone into the design of this unit, I can certainly bear witness to the success of the design as a whole in giving a high degree of realism in musical sound reproduction. In that it is definitely one of the few units that enthusiasts for what is called "high fidelity" must consider.

Gramophone Magazine – May 1954